How safe is my city?

In Lagos, Nigeria, as I was threatened with loss of life and limb if I dared roll down the windows of my cab in forty-degree heat, I thought longingly of my Bombay, where taxi drivers gave gyan and the wind whipped through broken windows, wiping out the stench of the city. In Jaipur, as a gang of biker boys rode circles around me in the middle of a busy street, with no one blinking an eyelid, I thanked my city for the basti boys I met the day of the deluge, who paid no heed to the wet T shirt outlining my breasts, and helped me negotiate the whirlpools that the gutters had turned into. In Bangalore as the city shut down way before the midnight hour, I recalled with fondness the late night butter chicken, bhurji pao and Bachelor’s strawberry cream. And as for Delhi, every single time I visited, I had the overwhelming urge to return home as soon as possible.

As a girl growing up in the early nineties, in the city then known as Bombay, I owned the nights, as I traversed its road and rail arteries – returning from work or play, sometimes drunk, occasionally sober- and always alone. The heady feeling of an empty compartment of the last train that chugged out of VT station way past midnight, with the wind blowing in my face and the world at my feet, is an experience that perhaps ended with my generation.

Sure Bombay is still safer than any other city in the country. But physical safety and mental security are two different beasts.

On the night the young photojournalist was raped, I was in a fashionable cafe, just a few mill compounds away, celebrating with girlfriends. I could have been in any world capital. Single women were working on their laptops undisturbed. Some were flirting with the bartenders. Others were whipping out credit cards to pay for cocktails consumed. Unknown to us, outside this picture perfect world, something sinister was afoot, and even though we had no knowledge of it then, we had a built in instinct. So as the friend I was to drop at a bus station emerged at midnight ready to leave, I looked at her little white dress, and she, by instinct went in and changed into pants for the long ride home. The heady feeling of the nights was gone forever. Replaced by caution, even fear.

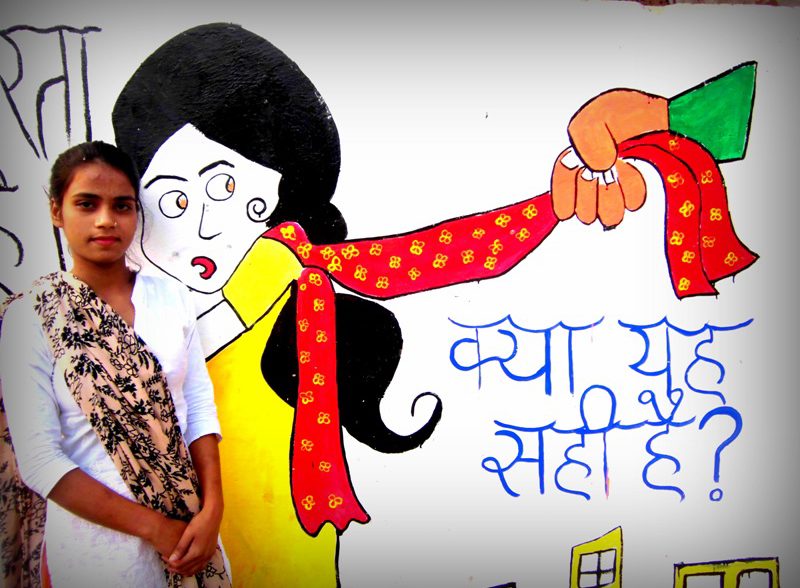

Gone also is a once certainty in this city- the goodwill of strangers. In a train compartment full of men, I was felt up from head to shoulder to breast by a transsexual begging for alms. I protested, for it is my right not to be physically touched by strangers, no matter the gender. The transsexual was aggressive and directed a loud voice and red eyes at me, while hurling choicest abuses. I stood my ground, probably in the naïve confidence of a compartment full of strangers, who I trusted to do the right thing. No a single man stood up in protest, or even voiced solidarity with me, even though many had been felt up in a similar manner minutes earlier.

Caution, I am reminded often, is the wise way forward. And I protest vehemently at the chains imposed on me, chains that I am still unused to. I scream from the rooftops that I will not let the city change me.

But inspite of myself, an evolutionary instinct of self-preservation is insidiously installing itself. And once minor, unnoticed events trigger of waves of caution. An unlit stretch of beach turns a bracing late evening walk into something menacing. The local drunk, once a source of amusement, now merits a crossing of road, a careering away from his threatening path. A reprimand to a male employee leaves in its wake fear of retribution.

Yes the city is still safer than any other in the country, but as our DNA’s change to negotiate the new reality, no amount of close circuit cameras or security personnel can make us feel safe any more. The fear has now crawled into our minds and hearts, and it is here to stay.

– Samina Motlekar blogs at http://saminasodyssey.blogspot.in