Reclaiming Art: An Evaluation of the Works of Nadine Mahoney

Kartika Puri, an undergraduate student at Ashoka University, explores writerly migrations between the spheres of art, society, and politics.

Reclaiming Art: An Evaluation of the Works of Nadine Mahoney

In Roman writer Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, attributed is the genesis of painting to a woman. The artist, infatuated with a man about to venture on a prolonged journey, traces the contours of his face on a brick wall, to keep alive his memory. Bearing in mind this mythological underpinning of Western art, it is regrettable to see the repute of female artists in the history of this realm.

Women had long been rendered solely the status of muses, providing creative impetus to Old Masters. With systemic obstacles that precluded them from professionally pursuing art, they were bound to this figurative Mount Olympias, in a manner not unalike Sisyphus’.

Numerous contemporary female artists recognise the deprivation in the legacy of art owing to the inequality of sexes. To unearth these former systems of hierarchy, they reassess classical art, and often in their reassessment make important alterations that undo those systems. For they accord to the muses of past a notable influence, thereby empowering them. Or they render ineffectual the authority of the Old Masters by opposing their rules. In consequence, they oppose the corollary of the Masters’ exclusivity in today’s art.

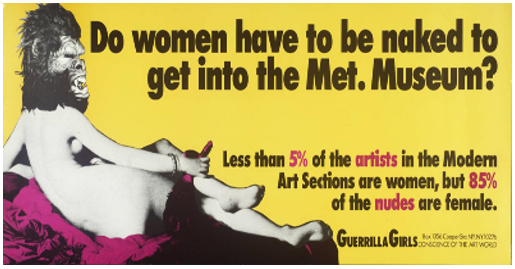

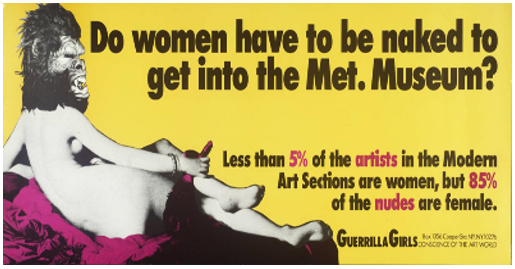

Image source: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/guerrilla-girls-do-women-have-to-be-naked-to-get-into-the-met-museum-p78793

The corollary of the past hierarchy and exclusivity in the artistic realm that continues to date

English artist Nadine Mahoney is one such contemporary female artist.

In her assessment of the art of past, Mahoney deftly reorients the master-muse relationship: It is the oeuvre of the male Old Masters that provides her with the creative impetus. For example, Parisian Impressionist Berthe Morisot’s “Portrait of a Lady” inspires two of her “Pretty in Pink” artistic endeavours; one an oil painting and another made on aluminium.

Berthe Morisot’s “Portrait of a Lady”

Mahoney chose Morisot’s painting as its female subject was limned without the nuances of a character. His was a facile depiction of women. In her article “Master as Muse”, Mahoney wrote, “Although a portrait, there was no clear identity to which woman ‘portrait of a woman’ was about…My practice is often steered towards arenas where identity is open to discussion”. She thus took it upon herself to prescribe the woman a personality and render her no longer two-dimensional by noticing and emphasizing subtleties in Morisot’s painting.

Of the subtleties in Morisot’s painting Mahoney wrote, “[It] seemed to be painted in mostly greys and browns, but the longer I looked I began to notice the browns had purple tones within them, and the beige has pinks. The pinks that made up the flowers were reflected throughout the canvas.” She selected this understated ornamental detail to guide the palette of her works. Her selection of pink renewed Morisot’s work within the arena of conventional femininity.

To render Morisot’s subject three-dimensional and emotive instead of the simplistically represented original, the bold monotone palette was created to accent the downplayed “sense of nostalgia the figure evoked”. Inspired by the subject’s dress, Mahoney used the folds of the fabric to redraw her face in a more genuine ardour. In addition, for her aluminium painting, her choice of the medium responded to the gaze of the subject.

Mahoney wrote, “In the flesh there was something quite confrontational about her despite her scale. I felt that the pink on aluminium responded to the sensation of being looked at.” The emphasis on the subject’s gaze through her choice of the medium reversed the customary dynamic of the subject-object. For no longer was the female ‘subject’ present for mere visual consumption by men, but it was also she who saw.

In this reassessment of an art created at the time of gross inequality and under-representation of women, contemporary artists akin to Mahoney use the process of drawing “to observe and distil an essence of what interests [them] in the original.” They emphasise what interests them, contort shapes, alter media, refigure the sentiment of the piece, introduce and eliminate elements, and by that endow the piece with new meaning, arguing against the earlier, less sophisticated opinions on women to increase comprehensiveness and universality in representation, and to carve a space in history that they were not given access to, but was always rightly theirs.

Sources:

http://nadinemahoney.com/blog/master-as-muse/