UNDER THE LIHAAF- The ‘threat’ of queer desire

Titas Ghosh is the Program and Outreach Officer at Delhi. She is a Political Science graduate who completed her Masters in Women’s Studies from Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. She gained experience working for a feminist organisation in Mumbai, as part of her Masters’ course-related fieldwork, that works with self-help groups in communities. Apart from this, she wrote her Masters dissertation on the lived experiences of women with breast cancer.

UNDER THE LIHAAF- The ‘threat’ of queer desire

INTRODUCTION

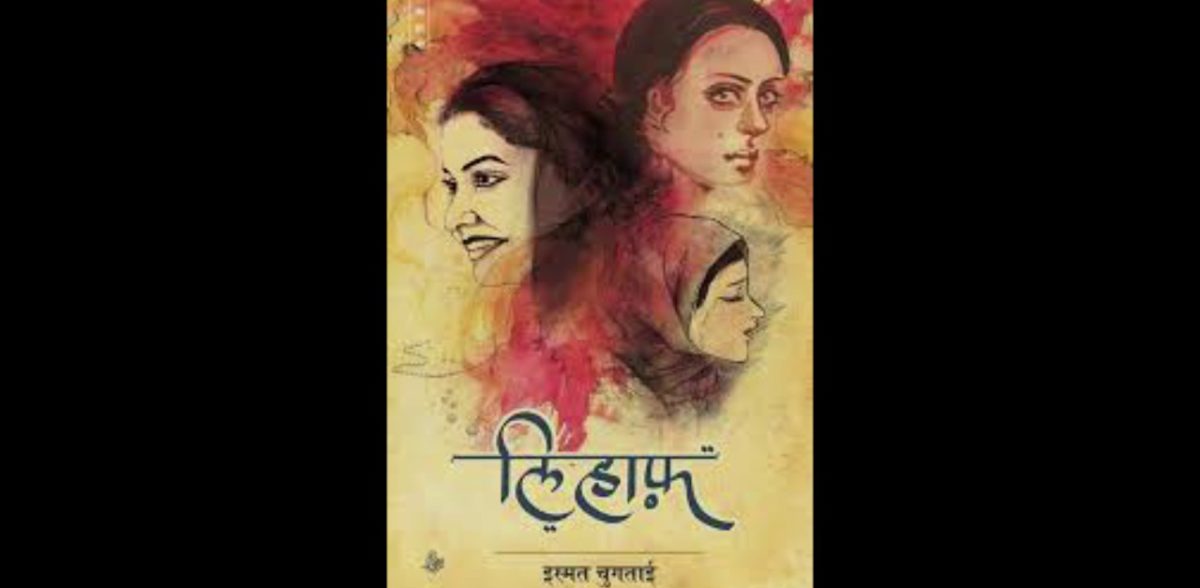

Lihaaf is not only one of Ismat Chughtai’s most celebrated works but was also one of the most controversial, for which she was summoned to court on charges of obscenity. Instead of apologizing, Chughtai chose to contest this charge and although the case dragged on for two years in Lahore, in the end she won the trial. It brought much notoriety upon her but towards the end of her life she was quite distressed by the fact that none of her other works received as much recognition as Lihaaf did.

The story of Lihaaf takes its readers behind the curtain, playing in the shadows of same-sex desire, and lifting the veil off of the forbidden desires of women in Muslim households. Written in 1941, it was published in ‘Adaab-E-Latif’ some time in 1942. The theme of the narrative, before the emergence of a strong public queer movement in India, was not just a taboo but even the existence of which was not acknowledged, or mentioned in the ‘polite’ society. It spoke of female sexuality defining the sexual needs of a woman, and also went many steps ahead ascertaining a conscious choice of an alternative sexuality instead of the conventional heteronormative behaviour. It not only spoke of alternatives for sexually repressed women in a patriarchal world but was also an attack on this world which was in turn shocked and understandably so, out of it’s own self-absorption.

THE NAWAB- EMBODYING THE HYPOCRISY OF VIRTUOSITY

Lihaaf tells the story of Begum Jaan who is married to an old Nawab Saheb ‘of ripe years’, belonging to a rich Muslim household, imprisoned in the same house by the regressive customs and patriarchal shackles of marriage imposed on a woman, made to suffer a life of isolation because her husband “tucked her away in the house with his other possessions and promptly forgot her”. The story narrated from a little girl’s perspective deliberately avoids an explicit articulation of the Nawab’s preoccupation. “Nawab Saheb had contempt for such disgusting sports. He kept an open house for students—young, fair and slender-waisted boys whose expenses were borne by him”. Chughtai artfully engages with questions of religious morality mediating it through the character of Nawab Saheb. Through the eyes of the little girl, she lays bare the hypocrisy and pretentiousness of the ‘virtuous’ upper-class elitist male garbed in religious rituals symbolising piety. The strong illusions of religiousness have translated to the morality of his social life in the eyes of the world underlined by references to his lack of sexual hedonism. “No one had ever seen a nautch girl or prostitute in his house”. Yet the Nawab has a ‘strange hobby’. Unlike other men of his social status, he never engaged in pigeon or cock fights. His only pleasure and desire, that remains unspoken of, is derived from providing an ‘open house’ for his male ‘students’. On the face of it, there seems to be nothing wrong with providing help to nubile, young boys. But Ismat Chughtai’s carefully chosen artful words presented in a tongue-in-cheek manner hint at the ‘sordid’ reality underneath this righteous behaviour. These are not boys who are described as naughty, quarrelsome robust kids but fair-faced and ‘slender-waisted’ young boys in ‘perfumed, flimsy shirts’. The description itself holds an unhealthy ring to it. Thus, the pretentious virtuosity of the Nawab is established from the absence of heterosexual relations in his life. The homosexual underpinnings of his social life strategically veiled from the hetero-normative society, goes unnoticed. While his homosexual exploits with young boys continued in the same household under the pretence of his so-called pedagogical endeavours, it was only his wife’s relationship with her maid that became a subject of whispered conversations.

BEGUM JAAN AND RABBU- EXPLORING UN-‘QUILT’ING SEXUALITIES

Begum Jaan, confined to a life of solitude and subjugation, did everything in her power to divert the attention of her husband from the ‘firm-calved, supple-waisted boys’ but she failed in all her attempts. The Nawab had no interest whatsoever in his wife’s life, or desires; she was merely a social stamp for the society’s acceptable standards of a heteronormative institution. Her presence in his life was completely dismissed and forgotten by him. This inequality in marriage not only symbolises the submissiveness and oppressed status of women but in this case, was also the impetus and motivation behind the commencement of Begum Jaan’s homoerotic relationship with her masseuse, Rabbu to fulfill her own sexual needs. Grasped by a sense of failure from her tiring attempts, Begum Jaan is reduced to a pitiable condition. But Chughtai does not portray her as a helpless woman but rather gives her the agency to find pleasure on her own terms. It was Rabbu who “rescued her from the fall”. She rediscovered sexual pleasure, the fulfillment of her own desires in Rabbu’s sensual oil massages, in her touch. Instead of giving in to the regressive customs of a patriarchal institution only by virtue of a legal relationship she shared with her husband, she goes on to paint a new image of a woman who is sexually liberated taking advantage of the segregated space in the household where she was ‘installed’ like a furniture by the Nawab. Thus the Zenana becomes a space for the expression of subversive desires, desires that a woman is forbidden to have, desires that are hidden under the quilt, and thus making the quilt an important symbol for the forbidden desires to slip into familiar spaces. The patriarchal society conditions women against the expression of their sexuality. The fact that Chughtai’s artfully concealed metaphorical description of female homosexuality is what brought censure upon her, summoning her to court is what establishes that female sexual desires hold much more of a threat to the conventional social formations than the idea of male homoeroticism.

Ismat Chughtai does not explicitly state the relationship Begum Jaan and Rabbu shared under the quilt; it is felt in the references and understood through the metaphors. “It was pitch dark and Begum Jaan’s quilt was shaking vigorously as though an elephant was struggling inside. “Begum Jaan…,” I could barely form the words out of fear. The elephant stopped shaking and the quilt came down”. Chughtai launches an attack into the society’s perception of a ‘diseased condition’ that homosexuality was considered to be without explicitly mentioning it. She uses the imagery of an elephant to portray a young girl’s sense of confusion. It is, at the same time, also symbolic of the confusion around the understanding of same-sex desire around that time. The visual of the elephant in the room was as disturbing for the little girl as it was for the readers of the time. The shadow of the elephant cast on the wall is used to subtly imply the physical relationship of the two women under the quilt.

THE NARRATOR- INVISIBLE SEXUALITIES TO IMMORAL SEXUALITIES

When Rabbu leaves to visit her son, who had supposedly refused the hospitality of the Nawab, for an indefinite period, there is a nasty turn of events. Firstly, Rabbu’s absence from the Zenana becomes the reason for the unsuspecting, confused young narrator to end up in the arms of her beguiling aunt. Also, this serves as a reminder of the pederastic practices of the Nawab, because it is mentioned that Rabbu’s son had also sought help from the Nawab and received many gifts from him but had then fled for reasons known to none.

A distraught and dejected Begum Jaan’s body aches at every joint in the absence of her personal masseuse until the narrator innocently offers her help to Begum Jaan to scratch her back. This escalates from an innocent playfulness to an unspeakable terror for the little child as her aunt hold the girl tightly against her body while the latter wails and weeps inside. This little girl who had no knowledge of the activities that went on under Begum Jaan’s quilt at night, could instinctively feel that there was something wrong when her aunt playfully refuses to let go of her while she made desperate attempts to leave. Thus the story also brings in questions of child sexual abuse. While Chughtai intricately brings in the anxieties around homosexual desire through the relationship between Begum Jaan and Rabbu, she carefully underlines the presence of consent and mutuality in the expression of sexuality. However with the child, the absence of consent is conspicuous and is not justified as a valid expression of sexual frustration.

CONCLUSION

Lihaaf redefines the relationship between a lesbian identity, the Muslim household and the patriarchal institution. The unfolding of homosexual pleasure in a dysfunctional Muslim household is based on the nonreproductive premise of the relationship shared between the Nawab and his wife. It is the heteronormative home that allows the space for homosexual relationships. The two women’s difference in class status is what enables them to get close to each other physically (giving Rabbu access to Begum Jaan’s body in order to facilitate and sustain the sexual relationship). The story brings in the possibility of a relationship between a woman and her servant, that which cannot be fathomed from the patriarchal perspective. The narrator also goes to describe the working class roughened and darkened body of the maid, comparing it to the glowing skin of Begum Jaan, trapped inside the house, never blemished by the sun. This description, in many ways, serves to create a gender binary, placing Rabbu in a masculine frame of character and Begum Jaan in a more feminine role.

Opinions expressed are of the author.